These images are derived from a PowerPoint presentation. They may be freely used for ringing educational and publicity purposes provided that the acknowledgements slide (or its wording) is also shown.

(Click thumbnail images to enlarge)

Title and acknowlegements

|

Title slide |

|

Acknowledgements |

Casting a bell

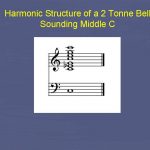

Bell tones and tuning

Notable bells

Full-circle ringing

Change ringing

Change ringing theory

|

Diagram of Rounds

‘Rounds’ can be represented numerically, starting with the bell with the highest note as number one. |

|

Diagram of 3 pairs of bells crossed from rounds

Simply ringing rounds becomes monotonous after a while. To break this up, the order in which the bells sound can be varied, but because of the physical constraints of the bell’s mechanism, each bell can only be moved one place at a time in the sequence. By swapping the three pairs of bells in rounds on six (1-2, 3-4 and 5-6), a row with a different sequence is created. |

|

Diagram of middle 2 pairs of bells crossed

Swapping the pairs back again would result in a return to rounds. Therefore, to create a new row, the bells sounding first and last in the sequence remain ringing in the same positions and the two middle pairs are swapped instead. |

|

Plain Hunt on 6: a complete lead

By alternately swapping three then two pairs as above, twelve ‘changes’ can be executed, one after the other, before returning to rounds. By ringing these rows, or ‘changes’, in succession, changing the order at each pull of the rope, the pattern of sound is varied and the most basic form of ‘change ringing’ is achieved. Each row is similar to a bar of music. Every bell must ring once only (at the same stroke as the rest) and can only ring again when all the bells have rung for that stroke. This pattern shows the most basic change ringing ‘method’ – analogous to a tune in conventional music – known as Plain Hunt or Original. |

|

Plain Hunt on 6: the path of the Treble

Method ringing requires each ringer to learn the pattern of successive changes. This is made even more challenging because, by tradition, no visual aids are allowed whilst ringing. The simplest method, shown in these diagrams, is known as “Plain Hunt”, in which each bell “hunts” from the leading position to the last position and back again. By superimposing a graph line over the path of one bell (No 1 in the diagram), the ringer can trace the position of his bell in the sound pattern relative to all the others. |

|

Path of the Treble plain hunting for any Minor method

By memorising this graph, the ringer has no need to memorise row upon row of complicated number patterns. |

|

Plain Bob Minor: paths of the Treble and the Two for a plain course

The ultimate goal of method ringing is to ring the bells in every possible order without repeating a row. In order to achieve this, ringers have devised ‘methods’, which are methodical systems of changing the order in which the bells are rung each time the ropes are pulled. Plain Bob Minor, rung on six bells, is shown in this diagram. Methods are the building blocks of change ringing. |

|

Grandsire Doubles: paths of the Treble and the Three for a plain course

When ringing a method the bells begin in rounds, ring changes according to the pattern set out in the method and return to rounds without repeating any row along the way. These changes produce musical patterns, with the sounds of the bells weaving in and out of each other. This method is known as Grandsire Doubles, which is rung on five bells, usually with a sixth bell, the heaviest of the ring – known as the Tenor, sounding at the end of each row. |

|

Two rows of Rounds and first 4 changes of Grandsire Doubles written in musical stave notation

The first few rows of Grandsire Doubles look like this in musical stave notation. The quarter rest at the end of each line depicts the customary ‘open handstroke lead’ used by most change ringers. This is achieved by all of the ringers slightly delaying each handstroke pull. |

|

Cambridge Surprise Minor: paths of the Treble and the Two for a plain course

Many more complex methods have been devised which provide more extensive sequences of changes before returning to Rounds. This example shows Cambridge Surprise Minor, rung on six bells. |

|

Phobos Surprise Maximus: paths of the Treble and the Two for the first 6 leads of a plain course

The diagrams for rather more complex and challenging methods, such as this one rung on twelve bells, often resemble the ECG trace for someone who has gone into cardiac arrest, and take a considerable amount of brain power to learn and ring. |

|

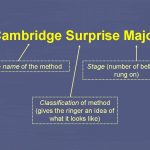

“Cambridge Surprise Major” – what the words mean

Each method has a “basis” to the way it is constructed. This creates various “classes” of methods that share common aspects of construction. Methods are referred to in full by their name, class (the type of line one can expect to see) and stage – the number of bells on which they are being rung. |

|

Some method names

Individual methods are often named after places (e.g. Kent, London), or after the person who invented them (e.g. Stedman, Annable’s London). This can lead to some very eccentric names! |

|

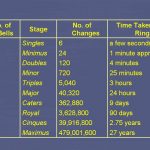

Time taken to ring the Extent on different numbers of bells

The table on this slide shows the number of changes possible without repetition on each number of bells. In this table the time take to ring each set of changes has been calculated assuming that the changes are rung at a rate of 24 changes per minute. |

|

The Extent on 8 bells

The longest peal ever on tower bells was rung at Taylors bell foundry, Loughborough, UK on 27 July 1963, consisting of all 40,320 changes possible on eight bells, in just under 18 hours. The rate of striking was 37 1/3 changes per minute. Pictured here is the band that completed this incredible feat of endurance and concentration: Front row L to R: Brian J Woodruffe (1), John M Jelley (2), Neil Bennett (3), Frederick Shallcross (4) Back row L to R: Paul L Taylor (bellfounder), John C Eisel (5), John Robinson (6), Brian Harris (7), Robert B Smith (8)(C), Peter J Staniforth (umpire) Details of the Extent on 8 bells The Extent on 8 bells was also the record length overall until 2 October 2004, in Coventry, when Philip Earis, Andrew Tibbits and David Pipe rang 50,400 changes (10 times the length of a standard peal) in 70 different Treble Dodging Minor methods on handbells in just over 17 hours – a striking rate of almost 50 changes per minute. An even more impressive feat of endurance and concentration, but at least they didn’t have to stand up all the time! |

New and old

Historic odds and ends

|

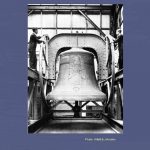

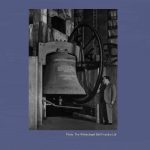

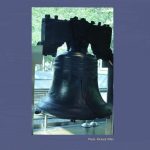

The Liberty Bell

The Liberty Bell is probably one of the best known bells in the world. It was originally cast in 1752 at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, London, by Thomas Lester to commemorate the 50th year of the existence of the State of Pennsylvania. After a stormy, eleven-week Atlantic crossing, it was cracked whilst being hung and tested in the tower of the Philadelphia State House. The bell was recast by John Pass and John Stow of Philadelphia, whose names appear on the new bell. Pass and Stow, who were not bell founders, added too much copper to the metal used to recast the bell and its tone proved to be unsatisfactory. The same founders recast it again, this time restoring the correct balance of copper and tin. Although the new bell did not wholly satisfy the Superintendents of the Pennsylvania Assembly, it was hung in the steeple of the State House in June 1753 and was the bell which became famous as the Liberty Bell by ringing to proclaim the Declaration of Independence on 4th July, 1776. The recast bell cracked in 1835. Rather than recast it yet again, an attempt was made to repair it by drilling a slot along the line of the crack to prevent the two sides from vibrating against each other. Two rivets were then inserted in the slot to try and restore the bell’s tone. Today, the Liberty Bell hangs on display in the Liberty Bell Pavilion, opposite Independence Hall in Philadelphia, and is still gently rung on 4th July each year. |

|

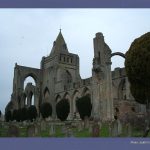

The First Peal

A ring of bells is sometimes referred to as a “peal”, but, more correctly, a peal is long piece of bell music consisting of 5,000 or more changes. One of the self-imposed objectives of method ringers is to ring a peal. The rules agreed by the Central Council of Church Bell Ringers, state that a peal should be rung continuously, without breaks, and by the same team of ringers throughout. The traditional length for a peal is related to the maximum number of changes possible on seven bells (5,040), which takes approximately three hours to ring. On seven or more bells, no repetitions of changes are permitted during the course of a peal and on lesser numbers only the minimum number of repeats are allowed. The first recorded complete peal was of Plain Bob Triples (rung on eight bells, seven bells performing the changes and the tenor, or largest bell, ringing at the end of each change “covering”), rung at St Peter Mancroft Church, Norwich on 2nd May, 1715. |

|

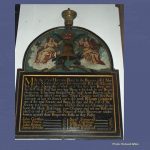

Ringers’ rules from the 17th century

During the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century, ringers began to form themselves into organised companies. Many of these groups had extremely elaborate codes of conduct, often written in doggerel and painted on boards hung in their ringing rooms. The set depicted here dates from 1694 and dictates, in delightful rhyme, the manner in which the ringers at Tong in Shropshire should behave. |

|

Tintinnalogia: or, The Art of Ringing

The first text book written on change ringing, Tintinnalogia, was published in 1668 and contains many sets of changes still rung today. See the full text of the 1671 edition of Tittinnalogia courtesy of Project Gutenberg. |

|

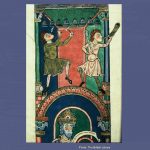

The Worms Bible

The Worms Bible was written in 1148 at the monastery of Frankenthal in the Rhineland, near Worms. It is a large Bible, over half a metre tall, preserved in two volumes. Its pages are littered with illuminations, including this one showing a musician playing a set of bells. The letters written on each bell, clearly show that by the twelfth century bell founders were capable of producing bells tuned to a musical scale. |